29th April 2021

In the fourth blog of our partnership with Make2ndsCount, we want to share reliable information surrounding the science behind Triple Negative secondary Breast Cancer (TNBC), as well as current and future treatments available. Nearly a third of people diagnosed with earlier stages of breast cancer will develop advanced disease1,2. Even though there are many people living with secondary breast cancer, it can often feel that it is excluded from breast cancer campaigns. Research has shown that women with advanced breast cancer often feel isolated and 67% of them feel like no one understands what they are going through3, 4.

“I want to be defined by what I am, not by what I am not” - Dr. Steven Isakoff (Breast Oncologist)

As summed up by Dr Isakoff, TNBC has been defined by not what it is, but what it isn't. So what is it not? TNBC means the growth of the cancer does not involve oestrogen, progesterone (hormones often associated with breast cancer) receptors and HER2 receptors. In this blog, we will be sharing with you accessible treatments for advanced Triple Negative breast cancer.

What is Triple Negative Secondary Breast Cancer?

Secondary breast cancer, also referred to as advanced, metastatic or stage IV, is cancer that has spread beyond the breast and nearby lymph nodes to other parts of the body. Breast cancer is usually categorised according to whether the cancer cells grow in response to different hormones or proteins. In TNBC, cancer cells do not express hormone’s or HER2 receptors.

TNBC represents approximately 10-15% of all diagnosed breast cancers 5,6, with over 8,000 cases diagnosed every year in the UK 7. This type of breast cancer seems to be more common in African 8,9 and Latina women 10, as well as in women under 40 11, 12.

Several studies have demonstrated that TNBC has the highest rate of recurrence within the first 5 years since diagnosis 13. Although advanced triple negative breast cancer is an incurable disease that has been characterised by the lack of targeted therapies, the discovery of new targets such as the protein PD-L1 or the presence of BRCA1/2 mutations, is changing this reality 14. These treatments will be discussed in the sections below.

Triple negative breast cancer is often genetically determined and appears to run in families 15. The most common genes that have been found to impact a person’s chances of developing breast cancer are BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. BRCA stands for breast cancer susceptibility gene. Among people with TNBC, 35% have the BRCA1 genetic variant and 8% the BRCA2 variant, whereas less than 10% of all newly diagnosed breast cancer patients carry these genetic mutations16.

Did you know?

The NHS offers genetic testing for BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene variants to women under 50 with triple negative breast cancer, including those with no family history of breast or ovarian cancer 17.

For more information about familiar risk and breast cancer genetic mutations, head to our previous blog on BRCA.

The analysis of your tissue sample from a biopsy or surgery will indicate that your tumour does not express an oestrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR) or human epidermal growth factor 2 (HER2). In your pathology results, you may read about the percentage of cells being positive for oestrogen and progesterone. If this percentage is less than 1%, the cancer is considered to be hormone receptor negative. For the HER2 protein, the result would be rated as 0, 1+ or 2+ to be considered HER2-negative18.

Triple negative cancer cells tend to look very different from normal breast cancer cells, which means that the cancer is classified as high grade (e.g. grade 3). Cells that behave in this way tend to have high levels of markers that indicate cell proliferation such as Ki67, p53+ and p63+. This means that the cells grow and divide quickly 19.

Want to keep track of all the information from your pathology report? With the OWise breast cancer app you can input your details and the app will generate a personalised treatment report based on your breast cancer subtype!

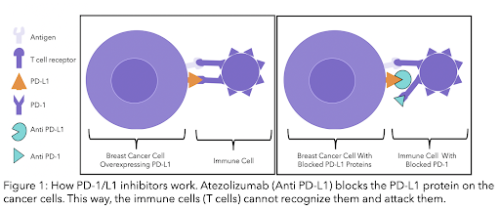

Recently, testing of the protein PD-L1 (anti-programmed cell death-ligand 1) has been approved in the NHS for TNBC patients 20. This protein is located on the surface of some cancer cells. PD-L1 protein is recognised by a receptor (PD-1) on the surface of a type of immune cell (T-cell). The immune system is the defence system of the body that protects us against pathogens and disease. Recent research has shown that if PD-L1 is blocked, these immune cells will recognise cancer cells as foreign and would attack them 21. Triple negative patients that are PD-L1 positive may benefit from newly developed therapies (see section and diagram below).

To better understand your pathology results, head to our previous pathology report blog.

Metastases is the spread of cancer cells to other parts of your body. Metastases in Triple Negative secondary breast cancer are common in organs such as the brain, liver, lungs and less frequently in the bone 22 .

We have compiled the treatments available through the NHS for TNBC secondary breast cancer. Current treatments aim to extend survival, maintain good quality of life and relieve symptoms. The treatment chosen depends on the extent of cancer spread and on the previous treatment you’ve received.

2.1 Chemotherapy

The common NHS chemotherapy regimen includes a taxane and an anthracycline. This is known as combination chemotherapy:

Anthracyclines can be cardiotoxic, meaning they can have a damaging effect on the heart. Therefore, if people are not suitable for anthracyclines (because of previous treatment or the toxicity to the heart) the treatments offered are:

Another treatment option is:

Capecitabine and gemcitabine are antimetabolite drugs. Antimetabolites interfere with DNA and RNA (genetic material) by acting as a substitute for the normal building blocks of RNA and DNA. When this happens, the DNA cannot make copies of itself, and a cell cannot reproduce 24.

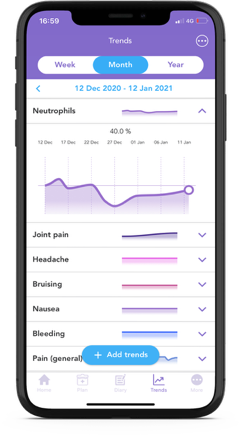

After two or more chemotherapy regimes, with an anthracycline or taxane and capecitabine, the drug eribulin (Halaven®) is recommended as a third line treatment 25. Please note that eribulin can increase your risk of infection as it lowers your overall white blood cell count, also called neutropenia. It is important to be aware of any potential symptoms of infection such as a fever, a sore throat, cough or diarrhea. It can also cause increased bruising and bleeding 26.

2.2 Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy uses the immune system to fight cancer. Therefore, it works by helping the immune system recognise and attack cancer cells. Some types of immunotherapy are also called targeted treatments or biological therapies.

It is the first immunotherapy available in the NHS for untreated secondary or inoperable triple negative breast cancer 27.

"The interesting part is what does immunotherapy do on top of what we see with chemotherapy? [...] The trial [combining chemotherapy plus immunotherapy before surgery] showed what we had hoped to see, in terms of increasing the number of patients responding to therapy, which is a very big step forward (Dr. Peter Schmid, Queen Mary University of London; director of the Atezolizumab III IMpassion130 clinical trial)

Atezolizumab is a monoclonal antibody and nab-paclitaxel is a chemotherapy drug. Atezolizumab blocks the protein PD-L1 which is responsible for preventing immune cells (mainly a type of immune cell called T-cell) from attacking human cells. PD-L1 is located on the surface of some cancer cells, and is recognised by a receptor (PD-1) on the surface of a type of immune cell (T-cell) (see figure 2 below).

Cancer cells trick the body into thinking they are normal cells by having PD-L1 proteins on their surface. If PD-L1 is blocked with atezolizumab, your immune cells detect cancer cells as foreign and harmful. Your body will then attack and kill these cancer cells28. Treatments can either block the protein on the cancer cell or the immune cell to stop the two from binding.

Secondary TNBC breast cancer tends to have earlier cancer recurrences that can often reach the lung and the brain. This therapy can increase overall survival by around 9.5 months of metastatic or locally inoperable TNBC patients that are PD-L1-positive 21.

Bevacizumab (Avastin®) is a targeted therapy. It targets a protein called vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) that helps cancer cells grow a new blood supply. Targeting VEGF reduces the supply of oxygen and nutrients so that the tumour shrinks or stops growing 29.

Bevacizumab can be prescribed in combination with the oral chemotherapy drug capecitabine when other chemotherapy options are not considered appropriate, or when they have been used within the past 12 months30.

If you have been prescribed bevacizumab in combination with a taxane such as paclitaxel, you have the option to continue with this treatment. However, this option is no longer recommended within the NHS as a first line therapy 30.

Chemotherapy targets all fast-dividing cells in your body. As cancer cells are fast-dividing, they are targeted and destroyed. But other fast-dividing cells are also affected, including hair follicles, the lining of the mouth, skin, nails and intestines. That’s why hair loss, brittle nails and diarrhoea are very common side-effects. Other very common side effects are sickness and vomiting.

Anthracyclines' side effects (e.g. doxorubicin) include vomiting, nausea and alopecia (hair loss). However, it can also cause heart function problems. This is why you might have heart tests to check the health of your heart before and during chemotherapy 31.

Some common side effects of Atezolizumab (Tecentriq®) are loss of appetite, difficulty breathing, fatigue, diarrhoea, feeling sick, skin changes, joint or back pain and urinary tract infections 32.

Bevacizumab’s side effects include neutropenia, bleeding, feeling sick, high blood pressure, headaches, tiredness, diarrhea, constipation, sore mouth or loss of appetite 29.

Do you know that you can track your side effects with OWise including neutropenia? With over 30 side effects and symptoms to choose from, you can track any changes and share these with your care team and loved ones. Better communication with your care team can make sure you receive the best care possible.

4.1 Sacituzumab Govitecan (Trodelvy®)

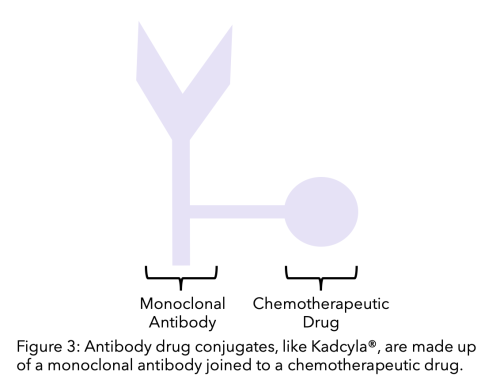

One of the most promising drugs for previously treated (at least two prior therapies) secondary TNBC is Sacituzumab Govitecan (Trodelvy®) that has recently been approved by the FDA in the US 33. Trodelvy® is a therapy that targets a new protein found in abundance in triple negative breast cancer cells: TROP-2.

This therapy is an antibody-drug conjugate which means that it is a monoclonal antibody linked to a chemotherapy drug. The antibody is specific for TROP-2, and the chemotherapy drug is SN-38. The monoclonal antibody targets and binds to the cell and the chemotherapeutic becomes active, killing the cell. This therapy can increase overall survival by around 12.1 months of metastatic or locally inoperable TNBC patients 34.

This therapy will undergo an accelerated assessment by the European Medicines Agency as well as by the MHRA and NICE to make it available in the UK this year 35.

4.2 PARP inhibitors

PARP (poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase) is a protein that helps both healthy and cancer cells repair DNA damage, allowing cells to survive and continue to function. PARP inhibitors work by blocking PARP proteins in cancer cells. This prevents them from repairing DNA damage, and often leads to cell death 36.

PARP inhibitors are a therapy for those with BRCA genetic mutations, which are common among TNBC patients. This is because PARP inhibitors are able to cause the death of cells carrying these genetic mutations. Two of the main PARP inhibitors are Olaparib (Lynparza®) and Talazoparib (Talzenna®). Both therapies are currently being assessed by NICE for metastatic HER2-negative breast cancer patients carrying BRCA1/2 mutations after chemotherapy 37,38. The publication of their decision has not yet been reported.

4.3 Pembrolizumab (Keytruda®) and Avelumab (Bavencio®)

Both pembrolizumab and avelumab have a similar mechanism to atezolizumab. Pembrolizumab blocks the action of the protein PD-1 and avelumab blocks PD-L1 (check the diagram above, Figure 1). Both of them have shown promising results in clinical trials for people with advanced triple negative breast cancer that have previously been treated with chemotherapy 39,40, and for those untreated in combination with chemotherapy 41. NICE may start to assess pembrolizumab in combination with neoadjuvant chemotherapy later this year 42.

4.4 Androgen Receptor (AR) directed therapies

Some triple negative breast cancer cells contain androgen receptors (AR). Hormones such as testosterone bind to these receptors and there is increasing evidence that they could play a role in the pathology of some triple negative breast cancers 43. Drugs that target these receptors such as bicalutamide or enzalutamide, already used in prostate cancer, could be repurposed for triple negative breast cancers 44.

We hope that you now better understand your treatment options and can feel confident in discussions with your care team. If you have any questions, make sure to note them down in the Questions list section of the OWise app, so that you can remember to ask them in your next appointment. At OWise, we want to make sure you are kept informed so make sure to follow our Instagram and Twitter for any updates. Any questions? Get in touch

Bibliography

[1] Arteaga, C., Sliwkowski, M., Osborne, K., Perez, E., Puglisi, F., Gianni, L. 2011. Treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer: current status and future perspectives. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 9, 16–32.

[2] Cancer.org. 2020. Breast Cancer HER2 Status | HER2-positive Breast Cancer. [online] Available at: https://www.cancer.org/treatment/understanding-your-diagnosis/advanced-cancer.html

[3] Novartis.co.uk. 2014. UK Here and Now patient survey. [online] Available at: https://www.novartis.co.uk/sites/www.novartis.co.uk/files/here-now-patient-survey.pdf

[4] abcglobalalliance.org. 2016. Global status of advanced/metastatic breast cancer [online]. Available at: https://www.abcglobalalliance.org/pdf/Decade-Report_Full-Report_Final.pdf

[5] Lund, M., Trivers, K., Porter, P., Coates, R., Leyland-Jones, B., Brawley, O., Flagg, E., O’Regan, R., Gabram, S. and Eley, J., 2008. Race and triple negative threats to breast cancer survival: a population-based study in Atlanta, GA. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 113(2), pp.357-370.

[6] Plasilova, M., Hayse, B., Killelea, B., Horowitz, N., Chagpar, A. and Lannin, D., 2016. Features of triple-negative breast cancer:: Analysis of 38,813 cases from the national cancer database. Medicine, 95(35), p.e4614.

[7] Icr.ac.uk. 2016. Promising drug target for aggressive ‘triple negative’ breast cancers identified. [online] Available at: <https://www.icr.ac.uk/news-archive/promising-drug-target-for-aggressive-triple-negative-breast-cancers-identified> [Accessed 9 October 2020].

[8] Brewster, A., Chavez-MacGregor, M. and Brown, P., 2014. Epidemiology, biology, and treatment of triple-negative breast cancer in women of African ancestry. The Lancet Oncology, 15(13), pp.e625-e634.

[9] Dindyal, S., Ramdass, M. and Naraynsingh, V., 2008. Early onset breast cancer in black British women: a letter to the editor of British Journal of Cancer regarding early onset of breast cancer in a group of British black women. British Journal of Cancer, 98(8), pp.1482-1482.

[10] Rey-Vargas, L., Sanabria-Salas, M., Fejerman, L. and Serrano-Gómez, S., 2019. Risk Factors for Triple-Negative Breast Cancer among Latina Women. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention, 28(11), pp.1771-1783.

[11] Keegan, T., DeRouen, M., Press, D., Kurian, A. and Clarke, C., 2012. Occurrence of breast cancer subtypes in adolescent and young adult women. Breast Cancer Research, 14(2).

[12] Siddharth, S. and Sharma, D., 2018. Racial Disparity and Triple-Negative Breast Cancer in African-American Women: A Multifaceted Affair between Obesity, Biology, and Socioeconomic Determinants. Cancers, 10(12), p.514.

[13] Lin NU, Vanderplas A, Hughes ME, Theriault RL, Edge SB, Wong YN, Blayney DW, Niland JC, Winer EP, Weeks JC (2012) Clinicopathologic features, patterns of recurrence, and survival among women with triple-negative breast cancer in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Cancer 118: 5463–5472.

[14] Malhotra, M., Emens. L. 2020. The evolving management of metastatic triple negative breast cancer. Seminars in Oncology. 47 (4): 229-237.

[15] Pogoda, K., Niwińska, A., Sarnowska, E., Nowakowska, D., Jagiełło-Gruszfeld, A., Siedlecki, J. and Nowecki, Z., 2020. Effects of BRCA Germline Mutations on Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Prognosis. Journal of Oncology, 2020, pp.1-10.

[16] Ellsworth, D., Turner, C. and Ellsworth, R., 2019. A Review of the Hereditary Component of Triple Negative Breast Cancer: High- and Moderate-Penetrance Breast Cancer Genes, Low-Penetrance Loci, and the Role of Nontraditional Genetic Elements. Journal of Oncology, 2019, pp.1-10.

[17] Nice.org.uk. 2020. Early And Locally Advanced Breast Cancer: Diagnosis And Management. [online] Available at: <https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng101/resources/early-and-locally-advanced-breast-cancer-diagnosis-and-management-pdf-66141532913605> [Accessed 9 October 2020].

[18] Cancer.org. 2020. Breast Cancer HER2 Status | HER2-positive Breast Cancer. [online] Available at:https://www.cancer.org/cancer/breast-cancer/understanding-a-breast-cancer-diagnosis/breast-cancer-her2-status.html [Accessed 7 October 2020].

[19] Badve, S., Dabbs, D., Schnitt, S., Baehner, F., Decker, T., Eusebi, V., Fox, S., Ichihara, S., Jacquemier, J., Lakhani, S., Palacios, J., Rakha, E., Richardson, A., Schmitt, F., Tan, P., Tse, G., Weigelt, B., Ellis, I. and Reis-Filho, J., 2010. Basal-like and triple-negative breast cancers: a critical review with an emphasis on the implications for pathologists and oncologists. Modern Pathology, 24(2), pp.157-167.

[20] Nice.org.uk. 2020. Atezolizumab With Nab-Paclitaxel For Treating PD-L1-Positive, Triple-Negative, Advanced Breast Cancer. [online] Available at: <https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta639/documents/final-appraisal-determination-document> [Accessed 9 October 2020].

[21] Schmid, P., Rugo, H., Adams, S., Schneeweiss, A., Barrios, C., Iwata, H., Diéras, V., Henschel, V., Molinero, L., Chui, S., Maiya, V., Husain, A., Winer, E., Loi, S. and Emens, L., 2020. Atezolizumab plus nab-paclitaxel as first-line treatment for unresectable, locally advanced or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (IMpassion130): updated efficacy results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. The Lancet Oncology, 21(1), pp.44-59.

[22] Liedtke, L., Mazouni, C., Hess, H., André, F., Tordai, A., A Mejia, J., Symmans, W., Gonzalez-Angulo, A., Hennessy, B., Green, M., Cristofanilli, M., Hortobagyi, G., Pusztai, L. 2008. Response to neoadjuvant therapy and long-term survival in patients with triple-negative breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 10;26(8):1275-81.

[23] Nice.org.uk. 2007. Gemcitabine for the treatment of metastatic breast cancer [TA116] | Guidance | NICE. [online] Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/TA116

[24] Cancer.org. 2021. How chemotherapy drugs work. Available at: https://www.cancer.org/treatment/treatments-and-side-effects/treatment-types/chemotherapy/how-chemotherapy-drugs-work.html

[25] Nice.org.uk. 2016. Eribulin for treating locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer after 2 or more chemotherapy regimens [TA423] | Guidance | NICE. [online] Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta423

[26] macmillan.org.uk. 2021. Eribulin (Halaven). [online] Available at: https://www.macmillan.org.uk/cancer-information-and-support/treatments-and-drugs/eribulin

[27] Nice.org.uk. 2020. Atezolizumab with nab-paclitaxel for untreated PD-L1-positive, locally advanced or metastatic, triple negative breast cancer. [online] Available at:https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/TA639 [Accessed 12 October 2020].

[28] Nice.org.uk. 2020. Improved deal means new treatment for a type of advanced breast cancer can be recommended by NICE. [online] Available at:https://www.nice.org.uk/news/article/improved-deal-means-new-treatment-for-a-type-of-advanced-breast-cancer-can-be-recommended-by-nice [Accessed 12 October 2020].

[29] macmillan.org.uk. 2021. Bevacizumab (Avastin). [online] Available at:

https://www.macmillan.org.uk/cancer-information-and-support/treatments-and-drugs/bevacizumab

[30] Nice.org.uk. 2021. Managing advanced breast cancer. [online] Available at:

[31] Cancerresearchuk.org. 2020. Doxorubicin [online]. Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/cancer-in-general/treatment/cancer-drugs/drugs/doxorubicin [Accessed 12 October 2020].

[32] Cancerresearchuk.org. 2020. Atezolizumab (Tecentriq). [online]. Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/cancer-in-general/treatment/cancer-drugs/drugs/atezolizumab [Accessed 12 October 2020].

[33] Oncologynursingnew.com. 2021.FDA Approves Sacituzumab Govitecan for Pretreated, Metastatic TNBC. [online]. Available at: https://www.oncnursingnews.com/view/fda-approves-sacituzumab-govitecan-for-pretreated-metastatic-tnbc

[34] Biospace.com.2021. FDA Approves Trodelvy®, the First Treatment for Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Shown to Improve Progression-Free Survival and Overall Survival. [online]. Available at:https://www.biospace.com/article/releases/fda-approves-trodelvy-the-first-treatment-for-metastatic-triple-negative-breast-cancer-shown-to-improve-progression-free-survival-and-overall-survival/

[35] Pink. pharmaintelligence.informa.com. 2021. Gilead’s Trodelvy To Test UK Innovative Drug Pathway. [online]. Available at:

[36] Cancerresearchuk.org. 2020. Olaparib (Lynparza) | Cancer Information | Cancer Research UK. [online] Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/cancer-in-general/treatment/cancer-drugs/drugs/olaparib-lynparza [Accessed 12 October 2020].

[37] Nice.org.uk. 2020. Project Information | Olaparib For Treating BRCA 1 Or 2 Mutated Metastatic Breast Cancer After Prior Chemotherapy [ID1382] | Guidance | NICE. [online] Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/indevelopment/gid-ta10342 [Accessed 12 October 2020].

[38] Nice.org.uk. 2020. Project Information | Talazoparib For Treating BRCA 1 Or 2 Mutated Advanced Breast Cancer After Prior Chemotherapy [ID1432] | Guidance | NICE. [online] Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/indevelopment/gid-ta10366 [Accessed 12 October 2020].

[39] Adams S, Schmid P, Rugo HS, Winer, EP, Loirat D, Awada A, Cescon DW, Iwata H, Campone M, Nanda R, Hui R, Curigliano G, O’Shaughnessey JO, Loi S, Paluch-Shimon, S, Tan AR, Card D, Zhao J, Karantza V, Cortes J. 2019. Pembrolizumab monotherapy for previously treated metastatic triple-negative breast cancer: cohort a of the phase 2 KEYNOTE-086 study. Annals of Oncology. 30(3):397–404.

[40] Dirix LY, Takacs I, Jerusalem G, Nikolinakos P, Hendrik-Tobias A, Forero-Torres A, Boccia R, Lippman M, Somer R, Smakal M, Emens L, Hrinczencki B, Edenfield W, Gurtler J, Von Heydebreck A, Grote HJ, Chin K, Hamilton E. 2018. Avelumab, an anti-PD-L1 antibody, in patients with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer: a phase 1b JAVELIN solid tumor study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 167:671–86.

[41] Schmid P, Cortes K, Pusztai L, McArthur H, Kümmel S, Bergh J, Denkert C, Hee Park Y, Hui R, Harbeck N, Takahashi M, Foukakis T, Fasching PA, Cardoso F, Untch M, Jia L, Karantza V, Zhao J, Aktan G, Dent R, O’Shaughnessy J. 2020. Pembrolizumab for Early Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine. 382:810-821.

[42] Nice.org.uk. 2020. Health Technology appraisal. Pembrolizumab in combination with chemotherapy for neoadjuvant treatment of triple negative breast cancer [online]. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/gid-ta10399/documents/draft-scope-post-referral[Accessed 12 October 2020].

[43] Rampurwala, M., Wisinski, K., O’Regan, R. 2016. Role of the Androgen Receptor in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 14(3): 186–193.

[44] Gucalp, A., Tolaney, S., Isakoff, S. J., Ingle, J. N., Liu, M. C., Carey, L. A., Blackwell, K., Rugo, H., Nabell, L., Forero, A., Stearns, V., Doane, A. S., Danso, M., Moynahan, M. E., Momen, L. F., Gonzalez, J. M., Akhtar, A., Giri, D. D., Patil, S., Feigin, K. N., … Translational Breast Cancer Research Consortium (TBCRC 011). 2013. Phase II trial of bicalutamide in patients with androgen receptor-positive, estrogen receptor-negative metastatic Breast Cancer. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research, 19(19), 5505–5512. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3327