Clinical Trial Phases and Drug Development

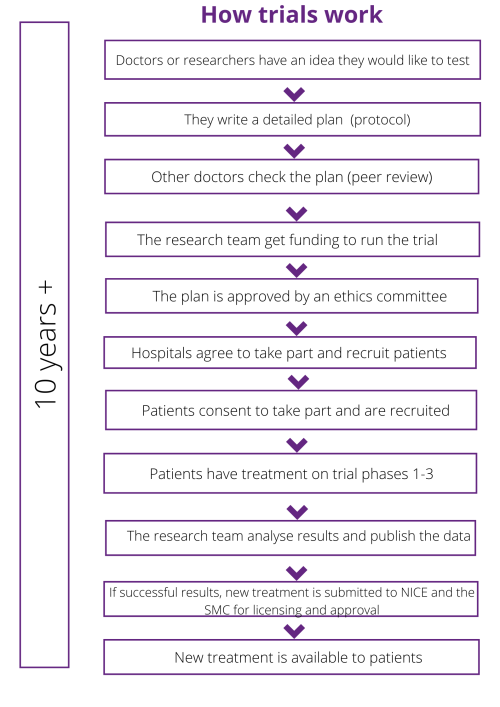

There is a very long and expensive development and approval process before a drug makes it to market. Most cancer drugs follow a similar overarching drug development path. This traditional pathway can take up to 15 years, but efforts have been made by industry to reduce this timeline.

There is a very long and expensive development and approval process before a drug makes it to market. Most cancer drugs follow a similar overarching drug development path. This traditional pathway can take up to 15 years, but efforts have been made by industry to reduce this timeline.

All drugs start in the lab – the lab may be private, or in a university, hospital or specialist cancer center – but generally this early research is no longer done by pharmaceutical companies. This starting point is called basic or pre-clinical research. There are usually 3 stages before a drug can be approved:

- Pre-clinical, or basic research

- Approvals and funding process

- Phase 1, Phase 2 and Phase 3 Clinical Trials

Pre-clinical, or basic research

Researchers test a new drug in the laboratory to see how effective it may be at treating a patient’s cancer. At this stage it may not be known if it is a potentially helpful drug, so patients are not involved at this stage.

Researchers test a new drug in the laboratory to see how effective it may be at treating a patient’s cancer. At this stage it may not be known if it is a potentially helpful drug, so patients are not involved at this stage.

This pre-clinical stage can take several years. For example, the University of Edinburgh project that we funded took 3 years to complete its lab work. If results from basic research studies are positive, the new drug or approach might then begin to be tested on patients in a clinical trial.

Approvals and funding process

All trials and studies go through an approval and funding process. This includes:

All trials and studies go through an approval and funding process. This includes:

- Peer review. The detailed plan which outlines how the trial will run is called the protocol, and this will be reviewed by an external group which includes scientists, doctors and patients. This review process by these external individuals is known as peer review. They will look at the trial design, whether the team has thought about all the possible issues and who they will recruit. Patient Information Sheets (PIS) are also developed at this point for recruitment.

- Ethical approval. The trial protocol and PIS are then reviewed by a Research Ethics Committee – they decide if the trial is safe and ethical, and whether it can go ahead or not.

- Registering the trial. There are a number of different international registries, including the WHO registry and clinicaltrials.gov.

Phase 1, Phase 2 and Phase 3 Clinical trials

If the drug proves to be potentially effective and beneficial in the laboratory and appears safe to give to patients, researchers might begin to treat a small number of patients on a phase 1 study, also known as early phase trials.

If the drug proves to be potentially effective and beneficial in the laboratory and appears safe to give to patients, researchers might begin to treat a small number of patients on a phase 1 study, also known as early phase trials.

These trials usually involve only one drug rather than a combination of drugs. Typically the main aim of a phase 1 trial is to investigate toxicity and a safe dosage of the drug.

In phase 1 trials researchers are aiming to find out the following:

• How much of the drug is safe to give to a patient?

• What are the side effects of giving the drug?

• Does the drug have any effect on the patient’s cancer?

Phase 2 studies can last from several months up to several years. They recruit more patients than a phase 1 trial and further investigate potential adverse effects and the correct dosage for patients. If the phase 2 study meets its objectives, the new treatment may continue onto a phase 3 trial.

Phase 2 studies can last from several months up to several years. They recruit more patients than a phase 1 trial and further investigate potential adverse effects and the correct dosage for patients. If the phase 2 study meets its objectives, the new treatment may continue onto a phase 3 trial.

In phase 2 trials researchers are aiming to find out the following:

• What are the side effects of the drug and how can they be managed?

• What type of cancer is the drug effective for?

• What effect is the drug having against the cancer?

Phase 3 clinical trials are larger and can last for several years – they may include several hundred to even several thousand patients.

The purpose of phase 3 trials is to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the drug in a larger group of people, and the results from these trials are typically used in the final application process. Phase 3 trials are often comparing the current standard of treatment against the new drug to see if it performs better.

In phase 3 trials researchers are aiming to find out the following:

• Is the new drug as good as the current standard of care treatment?

• Is it better than the standard cancer treatment?

• Does it have fewer side effects?

Once a new drug has successfully completed clinical trials, it will be submitted to the MHRA in the UK for authorisation. If licensed the drug company will then submit it to NICE in England and separately to the SMC in Scotland for use. This can lead to disparities across the UK where a drug might be available on the NHS in one country but not in another.